stipendiaten

özlem günyol & mustafa kunt

Die Ideen für ihre Arbeiten kommen zu ihnen, sagen sie, und dann beginnt das Ringen um eine ästhetische Form, die für beide Künstler stimmig sein muss. Özlem Günyol (*1977) und Mustafa Kunt (*1978) arbeiten seit 2007 zusammen in Frankfurt am Main. Sie haben an der Hacettepe Üniversitesi in Ankara studiert und an der Frankfurter Städelschule abgeschlossen, Günyol als Meisterschülerin bei Ayşe Erkmen, Kunt bei Wolfgang Tillmans.

In ihren Arbeiten zu gesellschaftspolitischen und historischen Themen untersuchen sie die Bedeutung von Sprache und Symbolen in kulturell unterschiedlichen Diskursen von Macht und Autorität. Für ihre künstlerisch präzise austarierten und medial vielseitigen Installationen mit skulpturalen Objekten, Print, Video und Zeichnung wurde das Künstlerduo bereits mehrfach ausgezeichnet, zuletzt mit dem von der Stiftung Kunstfonds gestifteten HAP-Grieshaber-Preis 2017 der VG BILD-KUNST.

Ihr ursprüngliches Stipendiumsprojekt, das sich mit der Problematik der Migrationsrouten von Tunesien nach Sizilien beschäftigen sollte, wurde von der Realität der vor dem Krieg in Syrien flüchtenden Millionen Menschen im Sommer 2015 eingeholt. Günyol und Kunt haben sich dieser aktuellen Situation gestellt und sich auf eine ungeplante Reise begeben, über die sie im Folgenden berichten.

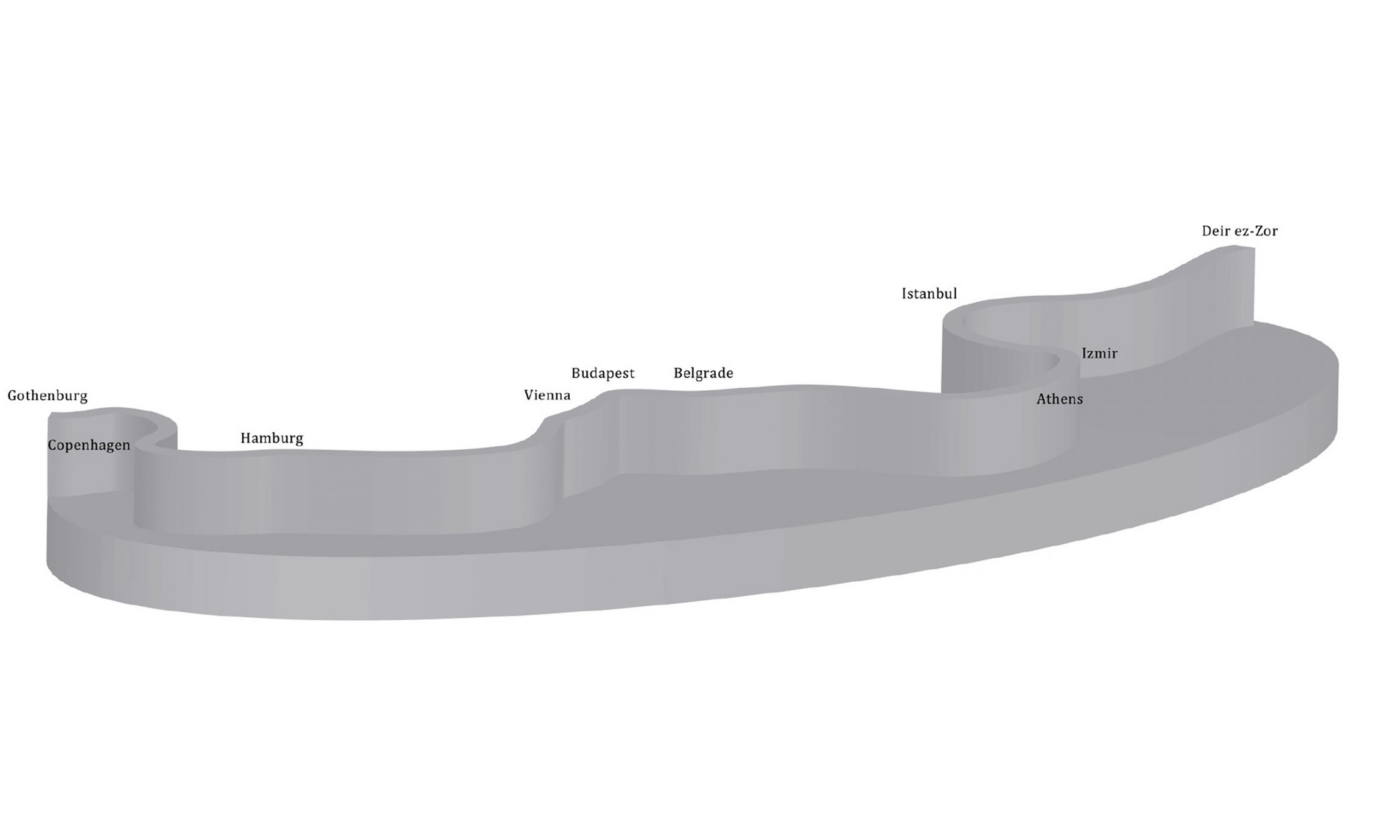

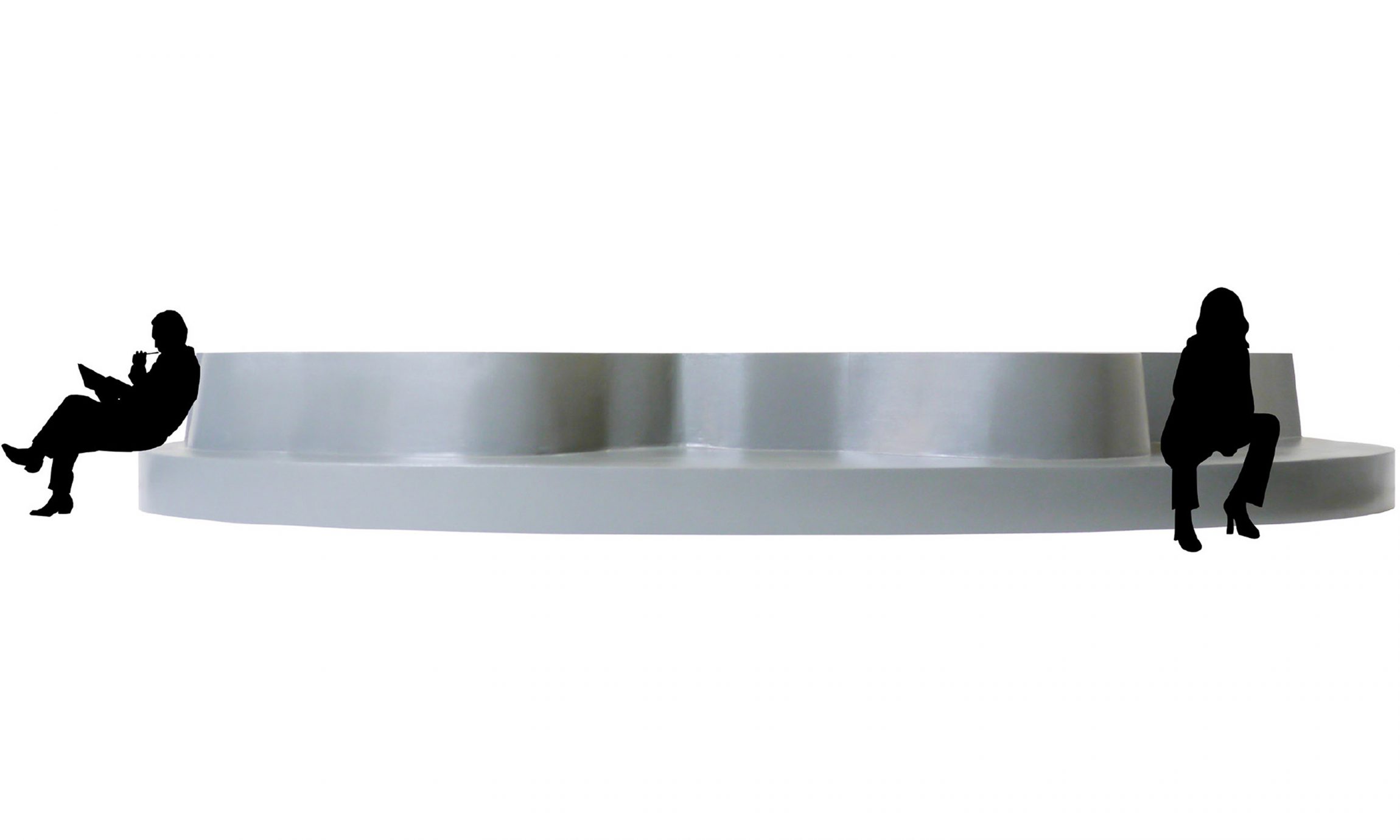

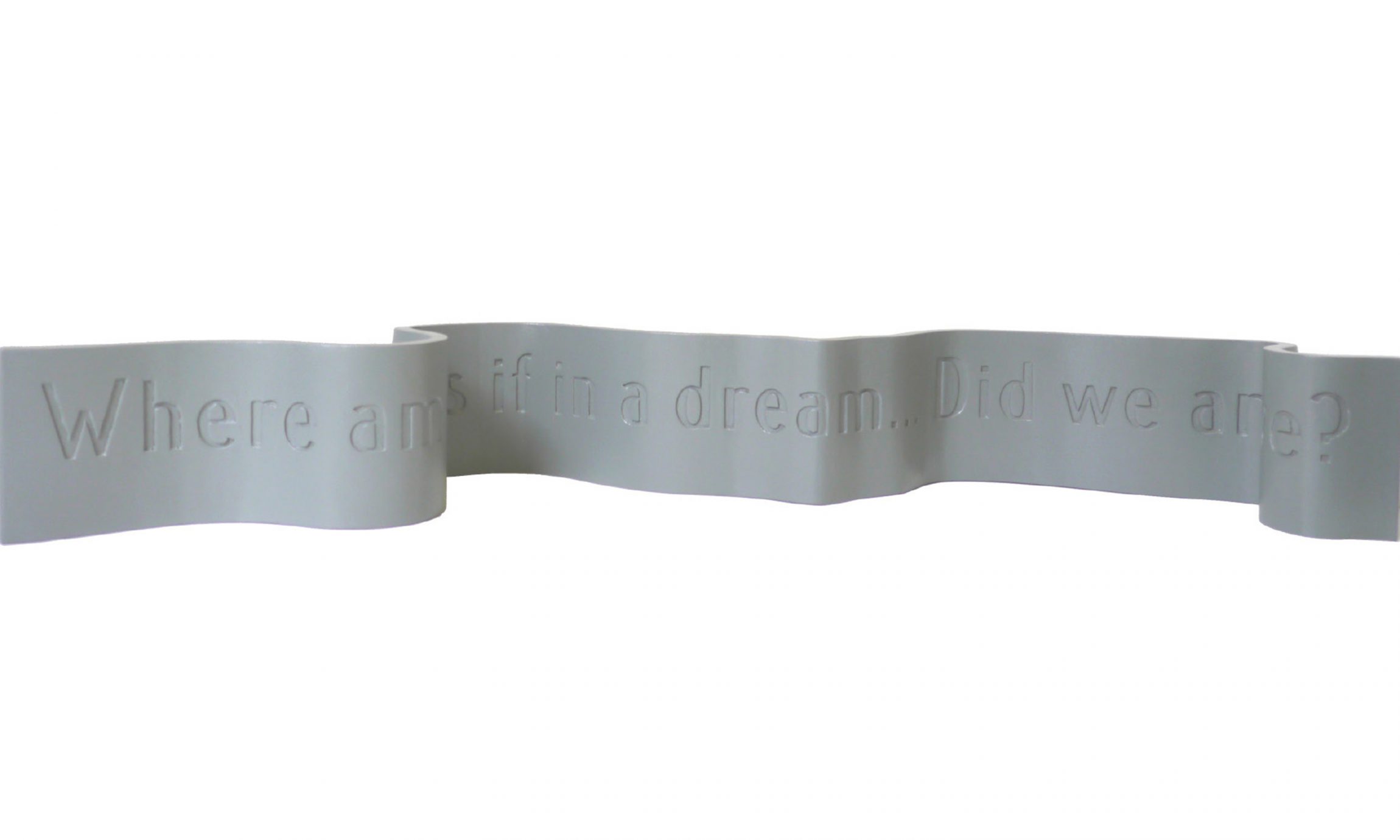

Where am I? As if in a dream… Did we arrive? (2016) ist eine der während ihres Stipendiums entwickelten künstlerischen Arbeiten. Sie besteht aus einer Sitzfläche für den öffentlichen Raum, die die lineare Form der Reiseroute einer Syrerin nach Europa nachvollzieht. Die Installation wurde im Rahmen des Wettbewerbs Kunstpfad Mainvorland der Stadt Rüsselsheim ausgewählt und realisiert. Sie wird in den kommenden Wochen am Mainufer unterhalb der Opelvillen in Rüsselsheim montiert werden.

Weitere neue und ältere Arbeiten von Özlem Günyol und Mustafa Kunt sind ab September in der Präsentation der 19. HAP-Grieshaber-Preisträger in Kooperation mit dem Deutschen Künstlerbund e. V. zu sehen.

Özlem Günyol and Mustafa Kunt: The Project

By the time we wrote and proposed our project Mare Nostrum (Our Sea) to the Hessische Kulturstiftung, the rescue operation Mare Nostrum of the italian navy was in full operation. However in 2014, the rescue operation Mare Nostrum ended and Frontex started a new operation called Operation Triton. At that time and especially after August 2015, the flow of refugees to the EU came to a height and large numbers of people attempted to make the crossing to Greece. Besides, the millions of people that had escaped from the war in Syria were already in Turkey. But as according to the system in Turkey, only the people coming from the West could get the asylum status, the millions of people received the „guest” status. However, being a guest means that you are expected to leave the place of visit after a period of time. The word “guest” creates an uncertain situation for the status of all those people. Thus, people started to set off from Turkey for a better and more secure future.

When all of these things were happening, we decided to stop our project Mare Nostrum (Our Sea) that we proposed to the Hessische Kulturstiftung in 2014 and decided to work with this ‚new situation’. After that moment, unlike a normal travel grant recipient, we had no specific project for the journey we were planning to make. In our case, the journey itself had to create the project/s.

The Journey

As a starting point we decided to visit Dikili (Turkey). Many migrants chose Dikili as their place to take a boat to Lesbos because Dikili is the nearest point to the island. Also, Dikili is the town; where the migrants were brought back from Greece to Turkey under the EU deal with Turkey in the spring of 2015.

During our stay there, we talked with Dikili residents about the ongoing situation. The Dikili experience was interesting in many ways. We witnessed that almost every evening the Turkish coastguard was going out to sea to search for border crossings. Meanwhile, we discovered a boat, which was laying in one of the small beaches in the city centre. This boat was caught by the Turkish coastguards when trying to cross the border to Lesbos. We were told that the coastguards saved the people in the boat and left the boat in the middle of the sea. Some time after, the boat crushed to the reefs. Only after that it was put ashore.

Next to these events, there were also some other discussions going on in Dikili about how the EU deal with Turkey was related to the inner politics of Turkey: Dikili is a left-oriented place. The Turkish government proposed to build a refugee camp in Dikili and according to the residents this proposal was made to change the city’s demographics.

After spending almost 3 weeks in Dikili, we went to Ayvalık to take the boat to Lesbos. During our stay in Lesbos, we have been to the Moria Refugee Camp, which is the biggest camp in all of the Greek islands and houses around 3000 people. Also we visited the Karatepe Refugee Camp, where mostly families stay and which houses around 400 people. It was not possible to enter the Moria Refugee Camp, but after long talks, it was possible to enter Karatepe Refugee Camp for a short period of time.

In the camp

As soon as we entered the camp, we started to question the meaning of our presence there. When walking through the camp, even directly looking at the eyes of the families sitting under their tents was hard. We became very aware of the difference between our and their situation of coming and staying there. The volunteers working in the camp told us that everyday there are crossings from Turkey to Lesbos. When every single day people risk their lives to cross the sea, how was it for us to come there? For us, it was just an hour and a half long trip to cross the sea to the island. As we both also have the German residence permit, we didn’t even need a visa. Because of such huge differences and inequalities between our station and theirs, we thought that whatever we’ll make, we must take this reality into account. We felt that we had no right to jump into the lives of those people just because they were in hard conditions. So, this was also the moment we decided, that our project/s would not contain or comprises of any documentations. We refuse to be the observer in this story. Not to create any project with the documentations did have other reasons too: We read lots of individual stories in the newspapers or in the blogs of people and we watched many documentaries in the meantime. We respect that a lot, but why did we start this journey? Our reason was pursuing an “art project”. So, we find it problematic to make an art project that benefits from the tragedy of the people, or that shows directly the ongoing situation like newspapers do, or that imitates the reality when the reality is there with its whole weight.

After Lesbos, we have been to Izmir. In Izmir, we visited the Basmane district, where migrating people met with the traffickers for a deal to cross the Aegean Sea. We also spend a day in the Dogancay Cemetery, where the municipality prepared the parcel No. 412 just for the graves of refugees in the middle of the graves of nameless people…

A couple of months later, we went to Çeşme and Chios for a couple of weeks. It was wintertime and the weather was mostly quite bad. There was a storm, but even then the crossings from Turkey to the Greek Islands were continuing. Travelling from Çeşme to Chios in stormy weather reminded us of what we were told during our visit in Karatepe Camp: people are mostly forced to make their journeys in such weathers in order not to get caught by the coastguards.

During the last two years, we continuously questioned ourselves to find ways that could touch both to our reality and to the reality of the migrating people. How easy was it for us to make the journey through the migration routes? What awaits the people that make it to Europe? What kind of a future? What were our first feelings when we came to Germany? How were we identified by the society and how did we identify the new society? What were our expectations at the very first moment of arrival?

Where am I? As if in a dream… Did we arrive? (2016)

Concrete sculpture, dimensions; 283 x 950 cm

The project concentrates on the common feelings experienced and the questions asked at the very moment of arrival. It comprises of 3 parts; the migration route of a Syrian woman to Europe, writings based on the interview of this woman with the BBC and the sitting area.

The work combines the route and the writing with a large sitting platform. Sitting, as an activity, associates with settlement and settlement is about becoming a place. In principle, if you become a place, then the place becomes you as well. It is an interrelationship. The work aims to embrace many people by combining the route with a half ellipse-shaped platform.

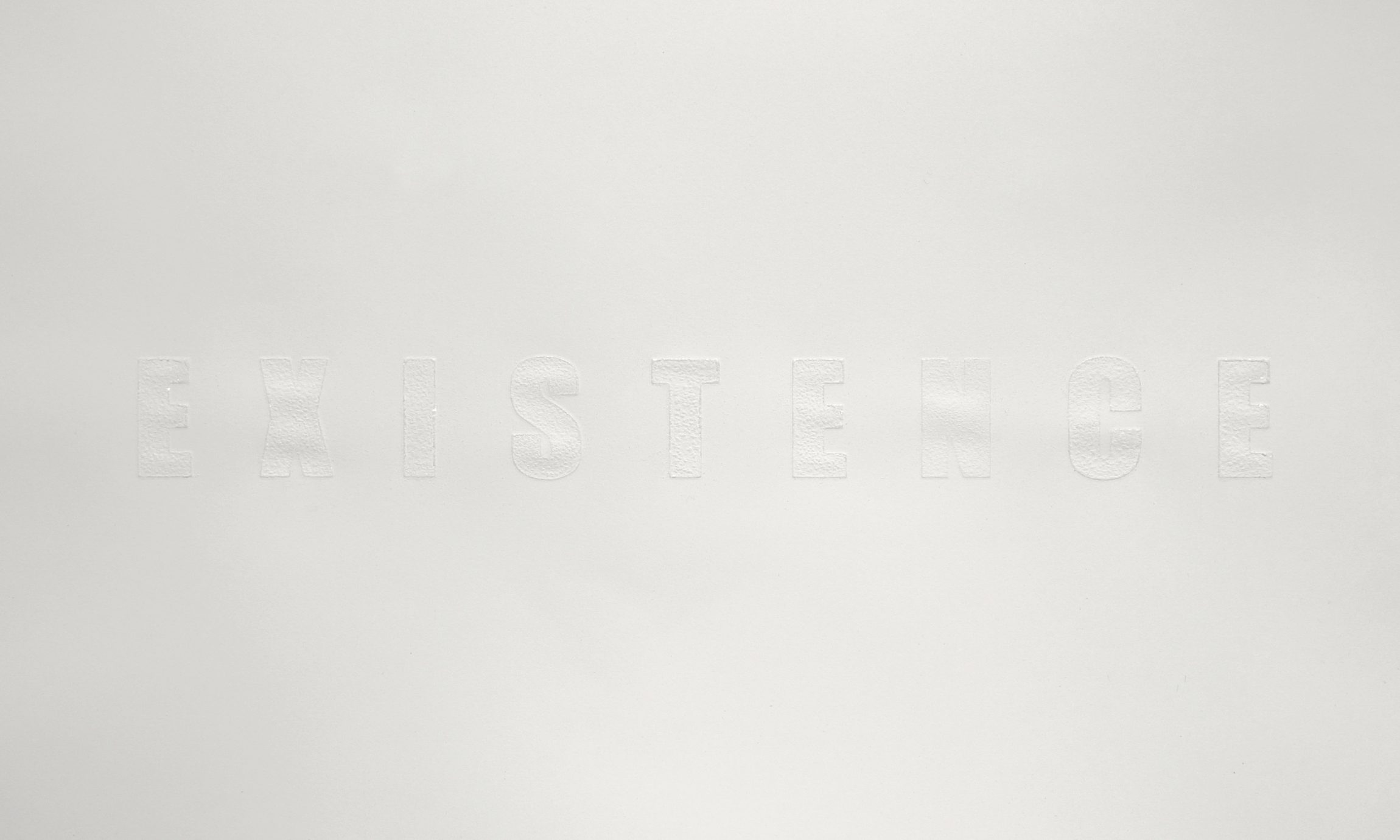

That which remains… (2017)

Sea-water on Arches Aquarelle paper, each; 56,5 x 76 cm

Words that are used to explain basic human rights such as; existence, privacy, life, liberty, equality, security, protection, movement are written with seawater taken from the Aegean Sea. The seawater that is used in the work is taken from Dikili and Cesme (Turkey), Lesbos and Chios (Greece).

Text: Özlem Günyol and Mustafa Kunt

- Özlem Günyol & Mustafa Kunt

- Beyond the Horizon

- 6. September – 27. Oktober 2017

- Deutscher Künstlerbund e.V.

- Geschäftsstelle

- Markgrafenstraße 67, Berlin

- Telefon 030 / 26 55 22 81

- Öffnungszeiten Di – Fr 14 – 18 Uhr und n. V.

- www.kuenstlerbund.de

- www.kunstfonds.de/foerderprogramm/stipendiaten/hap-grieshaber-preis/