scholarship holder christin berg

The aimless roaming of the streets of Paris and the cropped observation of petit d’oeuvres by the wayside has a long literary tradition in the French capital. In the figure of the flâneur, who strolls along the Parisian boulevards, but who also finds himself in the dark corners of the city, the modern metropolis comes to consciousness.

During her stay in Paris, Christin Berg (*1982) reflected on this modern figure, who has been influenced by authors such as Honoré de Balzac, Marcel Proust and Walter Benjamin and who has influenced the practice of numerous artists.

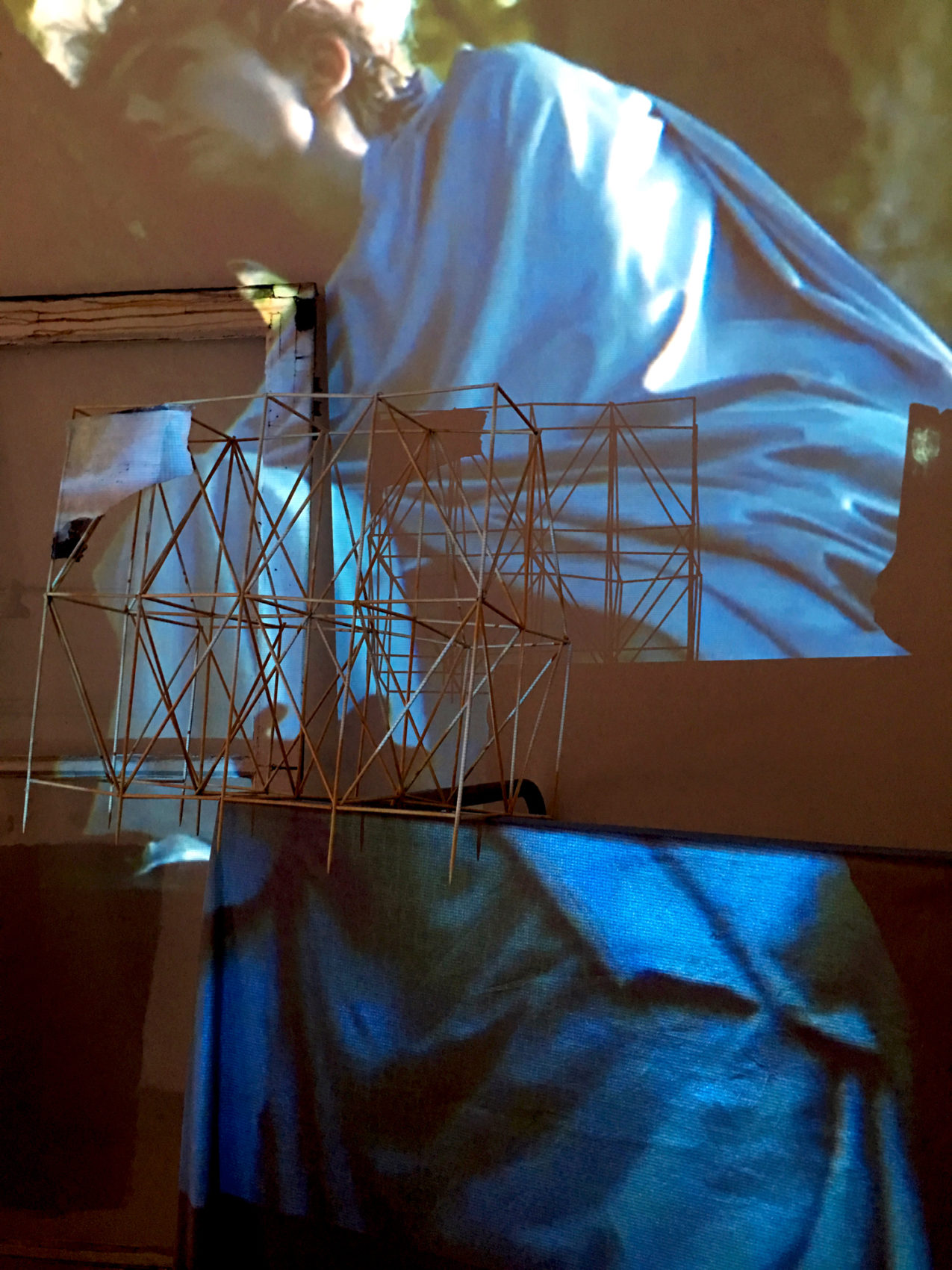

The protagonist in Berg’s latest film project is a flâneuse who moves through an apocalyptic fiction of the city of Paris. The art of movement between walking, dance, political or individual expression is one of the central motifs of her emerging film From the perspective of a walker or under the pavement lies the beach.

With the analog camera, the artist herself also went on daily forays through Paris. For Berg, such walks are often the beginning of her filmmaking career. With this routine she explores the aesthetics of her surroundings, which she desires for her expressive films. For the third film in her trilogy Fire on Air, Christin Berg collaborates with dancers, choreographers, musicians and other artists.

Christin Berg completed her studies at the Städel School in 2015 as a master student of Douglas Gordon. She previously studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and received a diploma in Scenography from the University of Applied Sciences and Arts in Hanover. In an interview with the French film scholar and intellectual Clara Schulmann, she talks about the rhythm of her work, about the connection between writing, music, drawing and dance, which she interweaves in her films to create a game of reality and fiction.

Clara Schulmann A starting point for your current film project From the Perspective of a Walker is a diary or chronicle that they have been writing since they arrived in Paris last year. What is the connection for you between writing and filming? And which artists are the inspiration for this personal equation?

Christin Berg For me, filmmaking means structure, but also uncovering chaos and complexity and integrating them into aesthetic schemes. Writing is a training, an extension of the mind into practice, into vita activa. It is a very private moment in which I can be extreme – without anyone noticing. For someone who doesn’t talk much like me, it is also an outlet for overstimulation or anger. My ambition to tell a story always comes from moods and reactions to my surroundings. Being here in Paris means dealing with the ancestors of this city and recognizing the foundation under the icing. In the off of what is in focus, I observe people and symbols and try to make this city recognizable in my abstract, cinematic description.

When writing, there is a beat like when playing a keyboard instrument. This rhythm is a premonition of the sequence of images and the later film editing. Film is always rhythm – beat on beat. I love to read poems by Patti Smith and listen to her poetry readings. In the process, images arise within me.

Susan Sontag was able to combine writing and filming; as in her film Letter from Venice (1983), which is based on her short story of the same name. I have long admired the filmmaker Nina Menkes, who also writes and shoots poetic images, as well as the poems of Pier Paolo Pasolini. Although I’m standing here on the ground and don’t have to go up to any world of gods. In Paris I met the group of Lettrist International around Guy Debord. This association from the 1950s called for the occupation and transformation of the city, for example by roaming the urban space for days on end. It was a kind of choreography.

Schulmann Writing is a solitary practice and filming is a collective one. Is that a rhythm that artists are used to living with?

Berg Being alone is an art from which one can draw strength, even filmmaker Tarkowski talked about it. I’m never alone in my studio work; every artist has his or her works, pictures, inspirations, or even the empty space that needs to be filled. Replacing the silence, the white sheet of paper, the black screen with something, that’s what it’s all about, becoming aware of an emptiness. A group has its own energies. That’s why it’s interesting with whom I cooperate as an artist, it has to be harmonious so that something new arises from the cooperation. Through the Swiss dancer Jasminka Stenz I got access to a dance school where changing choreographers warmed up the international dancers of this city every morning. Here I studied and drew movement sequences of ensemble work and discovered cooperation partners. Animate group dynamics. In Paris, together with filmmakers from the studio house of the Cité internationale des arts, I also founded a film salon called Collective Screening, our own nocturnal theatre cafeteria.

Schulmann In your project, Paris is both the city with a historical background in terms of artistic practices such as strolling and the city of the present with demonstrations or graffiti, full of “sound and fury”. In what way does your project attempt to capture these different dimensions?

Berg The protagonist of my film is a contemporary flâneuse and forms a strong counterpart in the sequence of artists’ groups and philosophers in Paris who reflect while walking, such as the Surrealists, the Situationist International or even Sophie Calle, who persecuted other passers-by and had themselves persecuted. Through explorations on foot I got to know and see this city. Film is technical, but the city of Paris is also a mood. In some texts I describe Paris like a walking person. There are limbs, a head, the centre, a heart that pulsates, and a back on which much rests. Also an ass that nobody is interested in. In this man-machine city, everything that makes life positive and negative is distributed.

Film is a layering of layers. I have defined every dimension: The historical background is the frame, the imagination and the black and white aesthetics are a depressive rage or current events, the sound is a glimpse of the future, and the editing is the call, an appeal perhaps.

Schulmann Your project deals with a possible end of the world that her protagonist faces. It has an amazing parallel to the current situation around the Corona pandemic. How and why did you come up with this possibility of an extreme scenario? Is it a possibility to increase the fictional level?

Berg I grew up in East Berlin. My generation enjoyed the freedoms after the fall of the Wall. But freedoms are not eternal. During my stay in Paris I corresponded with the cinematographer Jakob Stark at the North Pole. A research ship is frozen there for a year, taking measurements in the permafrost. The way in which the North Pole expedition provides predictions is haunting for the environmentally conscious person. Our finiteness and that of our resources is not fiction. Before the pandemic, the climate catastrophe had much public interest. Now what is closest to us is also the most tangible. On my exploratory walks through the city, I had the feeling that something intense had to be added to my fiction to represent a contemporary flâneur, away from the symbolism and splendour of this city.

The element of water is a constant motif in the film in various aggregate states: as breath, as an elixir of life, but also as a threat. In 1910 the last real flood of the Seine occurred in Paris. There is footage of how the stagnant water on the boulevards distorted the splendor of the buildings and how the inhabitants improvised during the catastrophe. My film projects are the result of research on current issues, I then interweave these documentary elements with fiction and develop a concise protagonist who can stand for our time.

In the past year, the image of life on the streets has constantly changed between the fire in Notre Dame, the yellow vest demonstrations, general strikes and the closure of public transport. This year, the Seine crossed the river banks, which are currently deserted. Our time is finite, and in the classic feature film it ends for the protagonist after only 90 minutes. In the film, time is skipped, but in real life, our 24/7, we skip through every second. Crises awaken an awareness of time.

Schulmann In your earlier projects sound seems to be a valuable ally. They sent me music that they are listening to right now. What plans do you have for the sound in this current film project?

Berg I love the sound of bass – deep, grounded, penetrating. In this film project, the sound symbolizes the rhythm of walking – beat, beat, impulse, step. It is the driving element. I often hear the same sound when writing as I do when editing a film. At the moment a lot of Éliane Radigue – the pioneer of electroacoustic music. But I also fall for the chansons of Barbara or the pieces of Laurie Anderson. With Eliane Radigue, I began to think about how a sound is recorded differently. We all see and hear differently. That’s what interests me in film, too: the different perceptions of two characters from which conflicts can arise. I often work with musicians, as I am currently working with the Canadian Ben Shemie or the composer Filip Caranica. From the beginning I thought about replacing dialogues in the film with music and strong physical expressions such as sign language. And communicating without dialogue also works between strangers, at demonstrations for example. To study the city on walks means for me above all to decipher the messages left or muted by its inhabitants.

Schulmann I sense a kind of sentimentality in your film description, and you also used this word in your diary. This supposedly feminine way of attracting attention interests me: your film is about a woman who is alone in the city. It reminds me of the female characters Cleo or Wanda in the films of Agnès Varda or Barbara Loden. Does this word mean something special to you?

Berg Cleo and Wanda vacillate between giving up on themselves and fighting against extreme existential pressure. They both let themselves drift and are at times the plaything of their surroundings. In filmmaking I look for heroic figures, female characters who grow and show strength in a situation. In the sense of the French le sentiment it is a mood that guides the protagonists in my films. I think it is less a female attribute than an exercise of the senses. In German, sentimentality has a melancholy sound, something negative. My characters are empathetic, attentive, but not sentimental. They sense their surroundings very precisely. Women in the public Parisian street scene have often been degraded to extras or prostitutes in literature, for example by the Surrealists.

Today the female sex is very present. Passivity should not be a characteristic of my heroes or anti-heroes, nor should it be a characteristic of our society in redefining hierarchies. The female protagonist in the current film project Flâneuse is socially integrated, respected, but she has a kind of premonition, because she perceives a change in social interaction. She is receptive to all kinds of stimuli and likes a close contact to the skin of others, but she herself does not come out of her skin. In this respect, we humans are perhaps all similar.