scholarship-holder giulietta ockenfuß

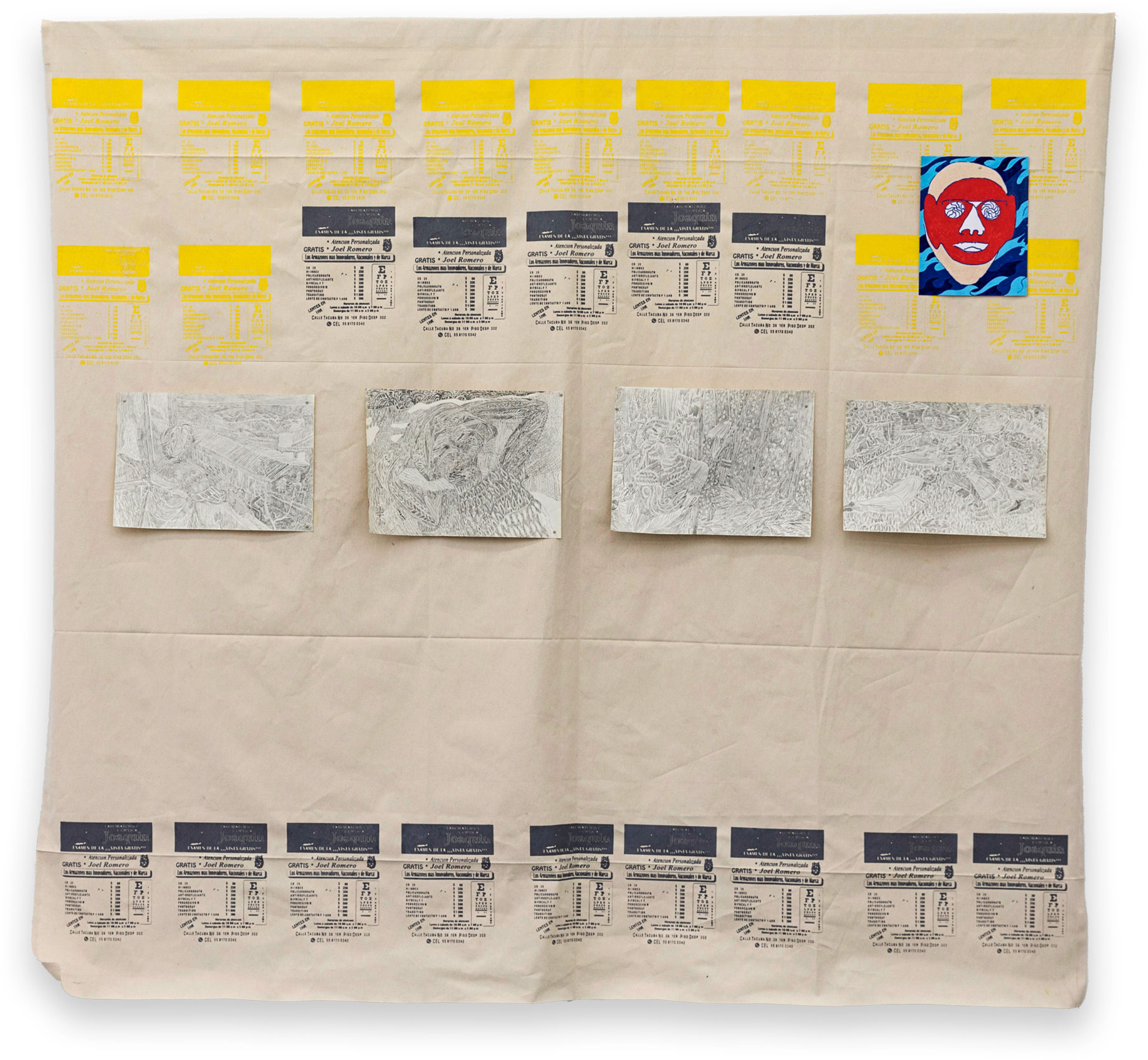

Giulietta Ockenfuss’s paintings and drawings are narrative. They tell dense, colorful stories about protagonists, whom they follow across different images in her work over a prolonged period. They are at once humorous, feisty, and confrontational, subverting the normalized modes of representation of female and male figures. Giulietta Ockenfuss combines her individual artistic approach with collaborations that sometimes last for years, in which performances and music play a central role. One such collaboration with Düsseldorf-based artist and filmmaker Catherina Cramer produced her first cinematographic work in 2020-1. Unleash the Beast is a video series in several parts that combines the formats of TV documentary and feature film. The overriding theme is the element of water, whereby the first chapter tells the story of a female aquatic ape whose path through life imagines a feminist-influenced history of evolution. The film footage was recorded during the artist’s two stays of several months each in Mexico, which Giulietta Ockenfuss undertook for research and work purposes courtesy of a travel bursary from the State of Hessen Cultural Foundation (Hessische Kulturstiftung).

In March 2021, Giulietta Ockenfuss talked to curator and critic Ania Czerlitzki in a meeting at the Liebfrauenberg, one of the nicest spots in Frankfurt’s old town.

Ania Czerlitzki Your latest work Unleash the Beast developed in collaboration with filmmaker Catherina Cramer, and you have already released the first part of the multi-part series in one of the online screenings organized by the Julia Stoschek Collection. The film footage for this was obtained during two joint stays in Mexico. What prompted your interest in the country? And how did you end up working together?

Giulietta Ockenfuß Painting and drawing form the starting point of my work. As part of that, since university I’ve been interested in Mexican modern art and its influence on Western art history. It was primarily my reflection on Mexican painting and my connection to it that gave rise to the idea for a trip to Mexico. At the same time, Catherina Cramer approached me because she wanted to make a film in Mexico, and from our time together at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, she remembered that I had studied the country and the culture and was familiar with the theme. At that point I had never made any films and I was excited about trying something that had never been part of my repertoire.

Czerlitzki Would you agree that you could describe the work as a „pseudo-documentary video series“?

Ockenfuß I find the term „pseudo-documentary“ problematic, although it’s clear what that impression stems from. I compile the work using fictional and documentary elements. For me and Catherina Cramer, it was important in our collaboration that these areas did not become too closely intertwined, rendering things unrecognizable. Naturally the fictional characters are invented figures; Certainly they are clearly recognizable as fantastical creatures. In addition to this, by way of distinction we work with real interview partners who report on their everyday lives.

Czerlitzki Is there a particular reason for working this way?

Ockenfuß We decided on this approach after the first research trip, because we’d noticed that we had certain expectations and impressions of Mexico, which in some ways did not correspond to our experiences there. That showed us that the structure of our work had to remain as open as possible. What’s more, we wanted to travel with lightweight luggage in the conceptual sense, but also with regard to the technology we used. This meant we were able to react quickly and flexibly to the different situations. Most importantly, though, we could approach people more easily and directly and participate in situations spontaneously. Our work method is open and processural, since we allowed ourselves to be led by our foreignness and the resulting curiosity that arose from that. My sketches and drawings helped me here in understanding the complex processes of self-reflection and in gaining numerous additional findings.

Czerlitzki How would you summarize the first episode of Unleash the Beast and how did you develop it?

Ockenfuß It very quickly became clear that we wanted to work with masks and at the same time to collaborate with artisans, since arts and crafts have a particular significance in Mexico. On this point, too, my drawings came to the fore again. I can speak Spanish, but there are language barriers, yet these could be overcome through the drawings. The masks that resulted from this represent the characters of the finished film. We developed the main character, a female aquatic ape, at the same time as the masks. She took on ever more concrete forms the longer we worked with the masks. The character is directly linked to the main theme of water and guides viewers through the film.

Czerlitzki Can you tell us more about this main character?

Ockenfuß We borrowed her from the theory proposed by the feminist writer Elaine Morgan (1920–2013). Morgan’s work was actually very popular during the 1970s, but wasn’t recognized by the scientific establishment. She identified the gaps in the explanations of the origin of human beings given to us by evolutionary science and utilized them for her own ideas. There are many theories, each of which is credible in its own way, but which cannot be definitively proven, since there are no descriptive sources. Scientific narratives can promote inequality between human beings and traditional power structures. This is where Morgan came in, further developing a thesis of evolutionary theory by Alister Hardy (1896–1985) in which female apes play a key role: This fantastical potential was really inspiring to us. We carved out the figure from Morgan’s writings and used it for the film.

Czerlitzki What is interesting to you personally in the figure of the female aquatic ape?

Ockenfuß When I came across this figure developed by Elaine Morgan, I found it very appealing because it was the first time that I was able to identify spontaneously with an origin narrative. In the evolutionary story of the hunter (homo erectus), I as a woman am not represented at all. The crucial thing about stories of origin is that is it a much-disputed field. All ideologies, from the different religions to the humanities to natural sciences, have their own answers to these huge, existential questions about our development. In contrast to my work as an artist, there is a monopoly of interpretation there. The ideologies are interested in their version becoming generally accepted and then constituting the truth. In the pre-Hispanic cultures of South America, for example, life was governed by the so-called codices. These are books compiled in pictorial language, including calendars, which describe the world and as part of that the development of the cosmos and humanity. The fact that the Spanish, when they came across them, burnt most of the codices is testament to this being a question of power. The majority of the remaining codices were then brought to Europe. I believe it’s no coincidence that two of the most important, the Codex Borgia and the Codex Vaticanus B, are located in the Apostolic Library in the Vatican. For many years, these codices were hard to access, but for some time now they have been available to the world online.

Czerlitzki It sounds like you have studied these codices pretty intensely, is that right?

Ockenfuß JYes, I have. What I’m interested in is how exactly early indigenous communities in Central and South America, like the Mayans, Aztecs or Mixtecs, encoded their knowledge. Incidentally, there is a research project at the University of Marburg and the University of Warsaw addressing quite similar questions – for example, what role these communication systems play in writing research and knowledge transfer. How did indigenous communities communicate with one another? These are questions I address and respond to in my art, too. These ancient systems do not aim to codify language, but rather convey their knowledge to recipients regardless of the language they might speak. In Mexico, even today, picture boards – so-called laminasare used in lessons and can be bought for a few cents in stationery stores. I believe these modern examples of pictorial script stem from a very ancient tradition.

Czerlitzki Another important topic relating to narration is tourism. In what way did this inspire you?

Ockenfuß The first chapter of Unleash the Beast simultaneously touches on tourists’ self-discovery trips. These are rooted in the backpacking tourism of the 1970s, which endures to this day, as Western tourists head for so-called exotic countries in an attempt to find themselves. In taking encounters seriously, even if they came about by chance, and creating interview situations, we are making an attempt to record this with a humorous and likewise critical approach.

Czerlitzki For you both, tourism seems to have been first and foremost a key to make you aware of your own position during your time spent working in Mexico. You frequently sought out people and places shaped by tourism.

Ockenfuß Yes, that was one point. We wanted to show that we are irrefutably also part of this group. We aimed to make it clear that we were approaching the context from the outside. What we didn’t want to repeat in this context was something that’s already become problematic in terms of alternative tourism, namely the eternal hunt for the next hot tip. Some places really should just remain a secret. There are specific cultural contexts in which the secret is definitely worth protecting.

Czerlitzki I’d like to hear a bit more about your way of working during filming.

Ockenfuß In our improvisation it became clear that the dialogue between us, the conversation partners, and between the fictional figures is very important. In parallel to this, the invented characters became ever more concrete. The first time that we held the mask of the main character in our hands was a heart-stopping moment. It felt alien. We didn’t make the mask ourselves; we actually got the craftsman Gilberto Linares to do it. By then using it or spontaneously handing it to another person and involving them in a conversation, we not only got to know the object, but also the fictional character inherent within it. This all formed part of the dialogue work.

Czerlitzki Through the moderation you undertook following on from your two stays in Mexico, you retain the option of critically questioning the film footage, commenting on it, and even seeing yourselves in an ironic light. It makes it clear that you are very well aware of the position from which you are narrating.

Ockenfuß Back in Germany, when we were going through the material, it became clear to us that we wanted to add even more narrative levels. We decided we needed a commenting voice in the video, like those you find in TV documentaries. It slots in and gives the audience certainty by explaining things.

What’s more important, however, is that the narrative level provides the option of making mistakes, perceiving them, reflecting on them, and dealing with them openly. That sets in motion a serious learning process. After all, in my role as storyteller, even afterwards I can still ask the question: „So what was going on in that situation?“

Czerlitzki Over the course of the discussion, you have talked about „dialogue work“. Diese Praxis ist für dich auch jenseits der Kooperation mit Catherina Cramer wichtig. Diese Art des Arbeitens läuft parallel zu deiner individuellen This is an important practice for you even aside from the collaboration with Catherina Cramer. This kind of working runs in parallel to your individual practice as a painter. How do you define both areas for yourself?

Ockenfuß I’m not someone who only works individually; I work on joint projects, too. In my experience, this provides for interesting interaction when strong, confident individual positions meet distinct attitudes. When you work with someone else, you are forced to clarify and to reformulate things that relate to the process of work. This results in a productive interplay. When you’re talking to somebody, you’re forced to define your position, and that’s very productive. At a certain point, though, the process needs to be completed.

Czerlitzki You were producing drawings at the same time as filming. How did your stay in Mexico and production of your film impact on your pictorial practice?

Ockenfuß For my images, figures and constellations of figures are crucial. The drawings and sketches I produced in Mexico, as well as the film, led to new characters popping up in my painting. These are not conventional human beings, but hybrid creatures somewhere between human and animal or animal and plant. This is a novelty in the substance of my work. One example is an almond blossom, which is in love with its own reflection. It is the protagonist of a second series which we, Catherina Cramer and I, are just starting to develop in parallel.